JONATHAN MANTHORPE: International Affairs

March 11, 2017

The United States is singularly prone to producing charlatans, messianic faith healers, snake oil merchants, flim-flam artists and all kinds of Pied Pipers who beguile, befuddle and bemuse large numbers of the population.

Donald Trump is a representative example of this flaw in the U.S. cultural DNA. But he is not the first American to have ridden charismatic demagogy into the White House, and nor is he, so far, the most horrific cult figure to feed his narcissism with the breath of the baying crowd.

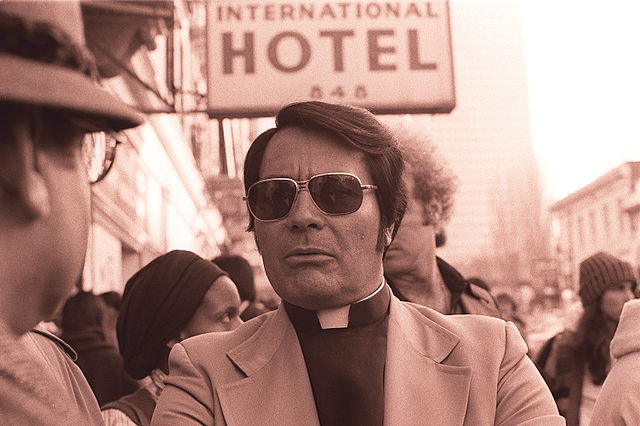

That crown must go to Rev. James Warren Jones, who on November 18, 1978, was responsible for the deaths of 918 people, including nearly 300 children. Almost all died by knowingly drinking poison on Jones’ instructions, with the parents killing their children first.

This was the largest number of Americans to die in a civilian act of violence until the attacks on New York and Washington in September, 2001.

Now, Donald Trump is no Jim Jones. The paths of the two men are different, even though Russia plays a significant role in both stories.

But the story of what led to the mass murder-suicide at the Jonestown commune in the jungles of Guyana in 1978 is a timely reminder that there are usually evil outcomes when large numbers of frightened and gullible people fall under the spells of immoral mesmerists.

Jones was born in 1931 and grew up dirt poor in rural Indiana during the Great Depression. Jones’ sense of being a social outcast pushed him towards communism, evangelical Christianity, and — unusually at that time – sympathy for the plight of African Americans. These three strands in his early life run through Jones’ entire story.

As a 20-year-old, while at Butler University, Jones joined the U.S. Communist Party in Indianapolis, and his emotional loyalty to the Soviet Union intensified during the McCarthy era of persecution of Marxists during the 1950s.

There can be no doubt that at this time, as a young idealist, Jones’ desire to pursue social change in the U.S. was entirely genuine. And with the political routes of communism or socialism closed to him, Jones opted to use Christianity.

“I decided, how can I demonstrate my Marxism? The thought was, infiltrate the church. So I consciously made a decision to look into that prospect,” Jones said later in a recording of biographical ramblings.

In 1952 he became a student pastor in the Methodist Church, but quickly fell out with his overseers because they wouldn’t allow him to have a racially integrated congregation.

As a result, a seminal moment came in Jones’ story when he attended a faith healing service at a Seventh Day Baptist Church. He was stunned by the amount of money the congregation donated while overcome by the full flood of the emotionalism of the event. Jones concluded that this kind of evangelical Christianity could provide him the money necessary to fulfil his Marxist social goals. He was well aware that the so-called healings were entirely fake theatrical events staged by the church with the only aim of separating the members of the congregation from their money.

Jones, like most of his kind, including Trump, was brimming with self-confidence and the capacity for self-promotion. He set out to stage his own massive theatrical faith healing event. It is a testament to Jones’ gift of the gab that he was able to get one of the most well-known and dynamic faith healing evangelists of the time, Rev. William M. Branham, to be the headliner at his “convention” in Indianapolis in June, 1956, that attracted about 11,000 people.

Jones continued to organize similar faith healing conventions and had soon made enough in profits to be able to start his own church. It started out as the Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel and went through several name changes until at the time of its death it was simply the Peoples Temple.

At this time – the late 1950s – Jones began minimizing his communist beliefs as the depredations of Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin became known, and Moscow’s violent response to the 1956 uprising in Hungary turned even committed Marxists away from the faith.

Instead, Jones began formulating what he later called “apostolic socialism.” He attended a service of the International Peace Mission at Delaware Street Temple, led by the African American cult figure “Father Divine.” Divine’s real name may or may not have been George Baker, but he preferred to refer to himself as “God,” the name used for him in his Federal Bureau of Investigation file.

Jones was bewitched by Divine’s outlandish, fire-and-brimstone preaching style, and adopted it himself. At the same time, Jones began imposing the brainwashing and systems of psychological control over his followers that have always been the hallmark of cults that prey on people with fragile self-esteem. Followers were pressed into seeing the Temple as their family, abandoning contact with their blood relatives and committing their lives to Jones’ goals.

At the same time Jones made the highly significant move into becoming an arm of the reformist establishment. Jones was rigorous in ensuring that about half the congregation of the Temple was African Americans, which brought him to the approving attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

In 1960 the Democratic Party mayor of Indianapolis appointed Jones director of the city’s Human Rights Commission. Jones became a highly public activist promoting the integration of churches, the police department, and public facilities such as restaurants, cinemas, theatres and parks. This was the beginning of Jones being seen by many in the American political establishment, especially Democrats, as a legitimate agent of social reform.

When it finally became apparent to many that Jones was nothing more than the leader of a venal, self-aggrandizing cult, this political support held back the denouement until disaster was inevitable.

In Indianapolis in the early 1960s there was a backlash against Jones’ integrationist activism. There was a number of apparent attacks on the Temple, though there is more than a suspicion that Jones was responsible for several of them to boost his mystique.

Probably, not all the racist daubings on the Temple walls and dead animals left on the door step were Jones’ fabrications because he started to show the signs of paranoia – the conviction that the shadowy “secret state” was out to get him – at this time. Though in cults, and, indeed, in ordinary life those with political power like to instill a degree of paranoia – of irrational fear – among the populous to make social control easier.

In 1962 Jones decided the Temple needed to find a new home. He spent much of the following year in Brazil looking, without success, for a suitable location. Back in Indiana, Jones decided to move the Temple to Redwood Valley, California, which was completed in 1965.

This was the beginning of the heyday of Jones’ cult. The Temple soon established branches in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which became the driving centres of the cult. The headquarters was eventually moved to San Francisco, which in the 1960s and early 1970s was the feeding ground for countless anti-establishment movement. Coupled with this was the establishment of an authoritarian organizational structure for the Peoples Temple, complete with armed guards for Jones, and a membership whose highly controlled lives were dedicated to garnering both donations for Jones and new members.

By the early 1970s, Jones claimed the Peoples Temple had about 20,000 members. This was an exaggeration, but the cult’s work with the homeless, the poor and addicts gave it significant influence with the cities’ and the states’ administrations. That gave Jones political clout, and in 1975 he mobilized his followers on behalf of the mayoral campaign of George Moscone.

After Moscone won a narrow victory he made Jones chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission. This seal of respectability brought Jones and the Peoples Temple the overt support of California Governor Jerry Brown — who has again held that post since 2011 — Assemblyman Willie Brown, and Harvey Milk, the first openly gay candidate for public office who became a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1978. Being seen with Jones became a necessity for political candidates, and in 1976 vice-presidential candidate Walter Mondale praised the Peoples Temple and its work. Later, First Lady Rosalynn Carter not only met Jones many times, she corresponded with him regularly on matters of national concern.

But Jones’ fame and success also brought disillusionment among some Temple members, and, as a result, scrutiny from the media and others.

In 1977 San Francisco Chronicle reporter Marshall Kilduff wrote a seven-part series about the Temple based on the testimony of defectors that they were sexually, emotionally and physically abused. The Chronicle, whose publisher and senior editors had been lobbied with great effect by Jones, refused to run its reporter’s articles. Kilduff took the material to the New West magazine. Just before publication of the articles, the editor of the magazine called Jones to read him some of the highlights. She later explained she did this because of all the letters of support for Jones the magazine had received, including from California Governor Jerry Brown.

Jones realized instantly that his game was up; publication of the details of how his scam cult operated would be the beginning of the end. While still on the phone with the New West editor Rosalie Wright, Jones scribbled a note to senior Temple members in the room with him: “We leave tonight. Notify Georgetown.”

Jones’ unsuccessful tour of Brazil did not end his hunt for a foreign sanctuary, safe, as he believed, from the scrutiny of U.S. intelligence and police agencies. In 1974 he had approached the Georgetown government of Guyana, the former British colony and only English-speaking country in South America. He had signed a lease to rent 3,800 acres of jungle-clad land – 15.4 square kilometres – about 240 kilometres west of Georgetown.

About 500 temple members had worked to establish what was officially called the “Peoples Temple Agricultural Project,” but which everyone called Jonestown. Jones said he envisaged his Guyanese colony as a rural communist utopia, and the embodiment of social and racial harmony. However, the reality was very different. The arrival of Jones and the other 500 exiles from California began the rapid decline of the experiment

Away from the U.S., Jones dropped all pretense of advocating “Apostolic Socialism” and became a pure Soviet propagandist. Evenings at Jonestown were spent with the enforced viewing of Soviet documentaries and preparation for what Jones said was a coming apocalypse. During what were called “White Night” sessions Jones commanded his followers to prepare for “revolutionary suicide” when U.S. agents attacked Jonestown. On many occasions followers were commanded to drink grape-flavoured Flavor Aid juice they were told was laced with poison. All did so.

The beginning of the end was in January 1978 when a defector from Jonestown, Timothy Stoen, joined with others to form a group of concerned relatives of followers of Jones. Stoen went to Washington, where he wrote a paper on Jones’ mistreatment of his followers. Stoen lobbied members of Congress and talked to officials at the State Department. California congressman Leo Ryan, understandably, was especially interested in Stoen’s case and took up the cause of the relatives of the Jonestown people.

In November 1978 Ryan led a fact-finding delegation to Guyana, which included several relatives and half a dozen journalists. The group arrived in Georgetown on November 15 and two days later flew to Port Kaituma, the nearest airfield to Jonestown. Jones sent cars for them and on the evening of November 17 hosted a reception for Ryan and his group in the central pavilion at Jonestown.

The group stayed overnight at Jonestown, but left hastily the following afternoon when Ryan was attacked with a knife by Temple member Don Sly.

Ryan insisted on leaving and with taking 15 Temple members with him who had said they wanted to go home to the U.S. Jones gave every appearance of acquiescing, and assigned transport to take the enlarged group back to the Port Kaituma airstrip.

But as Ryan and the group started to board the two planes at the airstrip, a contingent of Jones’ armed “Red Brigade” arrived and started shooting. Ryan and four others were the first to die as they tried to board a Guyana Airways Twin Otter plane. Meanwhile, one of the defectors turned out to be a plant. Larry Layton pulled out a gun and began shooting at other people who had already boarded the second plane, a smaller Cessna. Five people died in the airstrip shootings.

That evening, November 18, Jones ordered all members of the temple to gather at the Pavilion and in a 45-minute rambling speech, a recording of which was later found by the FBI, and told them to commit “revolutionary suicide.” He told them he had for months been negotiating with Moscow to try to arrange for the group to emigrate to the Soviet Union. However, since the air strip killings he did not believe the Soviet Union would take them, and that he expected U.S. agents would soon “parachute in here on us.” He warned the U.S. agents would shoot and torture them and their children. Those children that were not killed would be brainwashed and “converted to fascism.”

Tubs of the cyanide-laced Flavor Aid juice were produced and Jones is heard on the tape instructing followers to first kill their children and then drink the juice themselves. “We didn’t commit suicide,” Jones says at the end of the tape. “We committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.”

The body of Jones himself was later found sitting in a deckchair with a bullet wound to the head and a pistol by his side.

In all, 909 people in Jonestown died that day, 304 of them children killed by their parents. Four other people at the Temple’s office in Georgetown committed suicide on Jones’ orders.

But four of the Temple followers managed to survive by hiding under beds and in the jungle. Three young senior Temple officials were later arrested and detained by Guyanese police as they headed for Port Kaituma with $US550,000.00 and the equivalent of $US130,000.00. They said they had been instructed by Jones to take the money and give it to the Soviet embassy in Georgetown. The three also had letters for a Soviet embassy official saying the money was to go to the Soviet Communist Party, as was another $US7.3 million in accounts detailed in the letter.

Somehow in the story of Jonestown it has become fixed that it was poisoned Kool-Aid that was used for the mass murder-suicides. Hence, the grim lasting legacy of Jonestown is that people who blindly follow the orders of a demented leader are said to have “drunk the Kool-Aid.”

Copyright Jonathan Manthorpe 2017

Contact Jonathan Manthorpe, including for queries about syndication/republishing: jonathan.manthorpe@gmail.com

Further information:

Transcript of Jim Jones’ speech on “revolutionary suicide,” before the killings, Department of Religious Studies, San Diego State University: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Jones

Wikipedia page for Jim Jones: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Jones

~~~

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

~~~

Thank you to our supporters. To newcomers, please know that reader-supported Facts and Opinions is employee-owned and ad-free, and will continue only if readers like you chip in. Please, if you value our work, contribute a minimum of.27 per story/$1 per day pass via PayPal — or find more payment options here.

![]()

F&O’s CONTENTS page is updated each Saturday. Sign up for emailed announcements of new work on our free FRONTLINES blog; find evidence-based reporting in Reports; commentary, analysis and creative non-fiction in OPINION-FEATURES; and image galleries in PHOTO-ESSAYS. If you value journalism please support F&O, and tell others about us.