![Map of the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong, December 1941, by C. C. J. Bond / Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army - Stacey, C. P., maps drawn by C. C. J. Bond (1956) [1955].](https://canadianjournalist.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/1200px-Hong_Kong_18-25_December_1941.png)

November 11, 2016

On this day 75 years ago, 1,975 men, and two female nurses, of the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were steaming across the East China Sea in the New Zealand liner-turned-troop ship, SS Awatea.

This small rough-hewn and makeshift expeditionary force was bound for the British colony of Hong Kong and the Awatea was escorted by the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince Robert, a hastily converted merchant ship mounted with guns left over from the First World War. Somewhere, chugging along behind after leaving Vancouver a few days after the main force’s departure on October 27, was the freighter SS Don Jose, carrying the regiments’ 212 vehicles.

With war with Japan looming, the first instinct of British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had been to leave Hong Kong to its fate. But he changed his mind, and made the belated decision to reinforce the colony’s defences. He believed this would deter the Japanese armies lurking just over the colony’s northern border with China’s Guangdong province.

Thank you to our supporters. To newcomers, please know that reader-supported Facts and Opinions is employee-owned and ad-free, and will continue only if readers like you chip in. Please, if you value our work, contribute below, or find more payment options here.

Canada agreed to rustle up troops to bolster the Hong Kong garrison, then comprising about 12,000 men from a mishmash of units. Among them were only three top rank infantry units: the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots, the British Army’s most senior infantry regiment, and two highly regarded Indian regiments, the 5th Battalion of the 7th Rajput Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion of the 14th Punjab Regiment.

The only warplanes at Kai Tak Airport were some ageing torpedo bombers, and the Royal Navy’s once indomitable China Squadron was reduced to a destroyer, a few gun-boats, a flotilla of torpedo boats and two minesweepers.

Much has been written in the years since 1941 about the lack of preparedness and training of the men of the two Canadian regiments. While it is true they had no combat experience, unlike the battle-hardened Japanese they were about to meet, they were far from being raw recruits. They were put under the command of the highly experienced professional officer, Brigadier John Lawson, whose last position before the deployment had been the army’s Director of Military Training. Moreover, many of the commissioned and non-commissioned officers were veterans of the First World War.

In the weeks that followed the Canadians’ arrival in Hong Kong on November 16 they proved yet again that this country produces unrivalled infantry soldiers. And they made the defence of Hong Kong not only one of this country’s premier battle honours, they forged an indelible bond between Canada and Hong Kong.

Over 550 of the Canadians died in the battle for Hong Kong and in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps afterwards. An equal number were wounded. Of those killed, 283 are buried in the lovely and haunting Sai Wan Bay Cemetery in eastern Hong Kong Island, just below the jungle-covered hills they defended longer than anyone thought possible. Since then, of course, other bonds have formed between Canada and Hong Kong. Hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers have become Canadians in response to Britain handing back the territory to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. And hundreds of thousands of Canadians spend at least part of their lives living and working in Hong Kong.

The arrival of the Canadians on November 16, 1941, prompted the British commander, Gen. Christopher Maltby, to change his plans for the defence of the colony. He had proposed to leave only a token force on the mainland peninsular of Kowloon and the New Territories, and to concentrate the defenders on Hong Kong Island. Maltby now decided to deploy three battalions to defend the mainland territory along the famous “Gin Drinkers’ Line,” an 18 kilometre stretch of trenches, bunkers and machinegun emplacements.

A Canadian signals unit was assigned to this brigade, but Brig. Lawson’s two Canadian battalions and the British machinegun battalion, the Middlesex Regiment, became the core of the Island Brigade on Hong Kong Island. Brig. Lawson’s headquarters was set up roughly in the middle of the island on Wong Nai Chong Gap Road.

The next three weeks were the lull before the storm. There remained some hope, though not much, that the reinforced garrison would deter the Japanese. And there was among senior officers and colonial officials a dangerous underestimation of the audacity and fighting ability of the Japanese military.

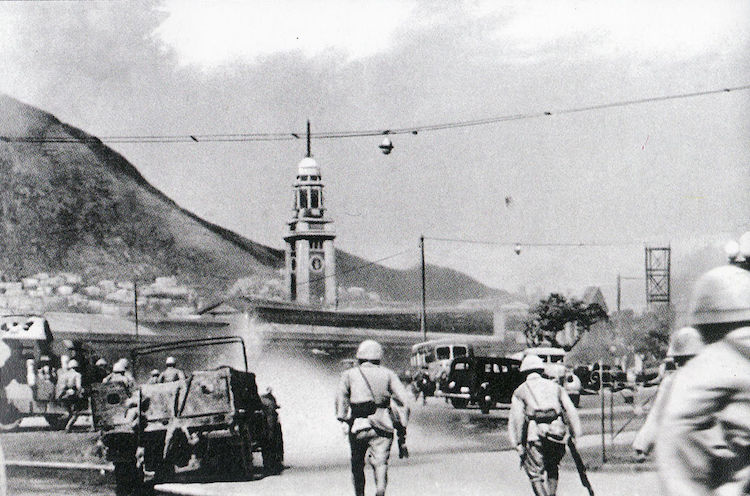

That insouciance collapsed on December 7 when the Japanese attacked the United States fleet in Pearl Harbour. So the Hong Kong defenders were alert and ready the next day, December 8, when the Japanese came pouring across the border from China.

Gen. Maltby hoped to be able to hold the Japanese at the Gin Drinkers’ Line for a week or more. At this point there was still some expectation of relief forces being hurried from other British Asian outposts, but that hope died when two ships heading from Malaya were sunk. And the hopes of holding the line across the New Territories vanished equally quickly.

Japanese fighter aircraft quickly established air superiority by destroying the few Royal Air Force planes and seriously damaged Kai Tak Airport along with them. This, as much as any of the actions in the battle, made the outcome inevitable.

On December 9 the Japanese showed just how serious was Maltby’s underestimation of their tactical fighting abilities. They launched a night-time attack on the Shing Mun Redoubt, the strategic hub of the Gin Drinkers’ Line, and captured it after heavy fighting.

The next day, “D” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers were sent from Hong Kong Island to bolster the defences, but on December 11 Gen. Maltby decided the Gin Drinkers’ Line could no longer be held. He ordered the withdrawal of the Royal Scots, the Rajuputs and the Punjabs down the Kowloon Peninsula and over to the island. This was covered by the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the troops along with most of their heavy equipment were successfully evacuated to Hong Kong proper.

The defences of Hong Kong Island were immediately reorganised. Canadian Brig. Lawson was put in command of the West Brigade, made up of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Royal Scots, the Punjabs and the Canadian signallers. The East Brigade was commanded by British Brigadier Cedric Wallis and comprised the Royal Rifles of Canada, and the Rajput Regiment. The Middlesex Regiment was under the command of Gen. Maltby at Fortress Headquarters.

The Japanese demanded the surrender of the defenders, and when this was rejected they began an artillery bombardment of the north shore – the Victoria Harbour side – of Hong Kong Island on December 15. After another rejected surrender, the Japanese troops began crossing the harbour on the evening of December 18, and after another successful night-time action were firmly entrenched on the island the following morning.

The Japanese troops then began committing the atrocities for which they became notorious throughout the Pacific War. About 20 gunners from the artillery Sai Wan battery, who had surrendered, were executed. The Japanese went on that night to kill the medical staff and wounded soldiers at the Salesian Mission hospital on Chai Wan Road. Among those killed were a Canadian doctor and two wounded men of the Royal Rifles.

Over the next days of the battle the Japanese continued to kill medical staff, wounded soldiers and prisoners as they were captured. Well over a hundred civilians and prisoners are believed to have been killed by the Japanese during the battle, and many more were killed deliberately or through murderous ill treatment while in captivity during the rest of the war.

On Hong Kong Island, the Japanese troops quickly took control of high ground from Jardine’s Lookout, above Causeway Bay and on the road to Brig. Lawson’s headquarters on Wong Nai Chung Gap Road, to Mount Parker in the east, on the approaches to Tai Tam Reservoir.

Brig Wallis then ordered the East Brigade to withdraw towards the Stanley Peninsula, which extends from the south-centre of the island, and from where he hoped to launch a counterattack. Unfortunately, crucial arms and equipment were lost during the withdrawal, and communications between the two Brigades were cut as the Japanese pushed through to reach the island’s south coast at Repulse Bay on December 19.

East Brigade had been seriously mauled and depleted in the course of the fighting. The Rajputs were virtually wiped out defending the island’s northern beaches against the Japanese invasion on December 18. There were some surviving units of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps and some machinegun units from the Middlesex Regiment. The men of the Royal Rifles of Canada were exhausted, had had little sleep and had existed on field rations for several days.

Even so, over the following few days East Brigade led by the Canadians, attempted to drive the Japanese off the high ground and to re-establish contact with West Brigade. They first pushed along the shore from the peninsula to Repulse Bay, and managed to drive the Japanese from the famous Repulse Bay Hotel.

But the Royal Rifles were unable to drive the Japanese from their dominant positions in the hills, and had to withdraw to the Stanley Peninsula. Another attempt was made on December 21 to link up with West Brigade with a more easterly push towards Wong Nai Chung Gap Road. In heavy fighting the Royal Rifles managed to dislodge the Japanese from several of the jungle-clad hill tops. But the Canadians could not hold the positions, especially after they ran out of mortar ammunition.

On December 22 volunteers from the Royal Rifles made a night-time attack and captured Sugar Loaf Hill on the approaches to Stanley Peninsula. The Canadian troops were exhausted, while the Japanese had been reinforced and received supplies of arms and ammunition.

Brig. Wallis ordered the remnants of his command to withdraw to Stanley Peninsula, which the Brigade defended until the end, including a fierce action with many losses on Christmas Day.

Meanwhile the West Brigade was also heavily mauled after the Japanese successful amphibious attack across the harbour on December 18. On December 19, “A” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was ordered to clear the Japanese from their dominant position on Jardine’s Lookout and to then move on to retake Mount Butler en route to Tai Tam Reservoir, with the intention of reconnecting with East Brigade.

The initial attack was successful. Thirty troops led by 42-year-old Company Sergeant-Major John Osborn, an Englishman who emigrated to Canada in 1920 after serving in the Royal Navy in the First World War, seized Mount Butler. But the group was quickly surrounded by Japanese troops, who lobbed grenades into the Canadian position. Osborn caught several of the bombs and threw them back. But then one landed just out of his reach. He shouted a warning and threw himself on top of the grenade, which exploded and killed him. After the war Osborn was awarded the Victoria Cross and there is a monument to him in Victoria Park, just above Hong Kong’s Central business district.

On the same day, December 19, a large detachment of Japanese troops surrounded Brig. Lawson’s headquarters on Wong Nai Chung Gap Road. A company of Royal Scots attempted to break the encirclement, but were unable to do so. Late in the morning, with the Japanese firing into the command post from almost point-blank range, Brig. Lawson sent a message to Gen. Maltby that he was “going outside to fight it out with the Japs.”

Lawson, armed with two revolvers and with two of his officers, including his deputy Col. Patrick Hennessy, at his shoulders, rushed outside. All three were killed instantly.

A British colonel from the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps was appointed to command West Brigade.

“D” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers held out around the Wong Nai Chung Gap Road position for three days and only surrendered after they had run out of ammunition, food and water. The Japanese found only 37 wounded Grenadiers in the captured emplacements.

Meanwhile the remainder of the Grenadiers, together with the Royal Scots, elements of the Middlesex Regiment and what was left of the Indian battalions formed a defensive line centred on Mount Cameron and running from Victoria Harbour at Wan Chai to the south coast near Aberdeen Harbour. The defenders were under constant attack from dive bomber aircraft and mortars for three days, before the left sector above Wan Chai was breached by the Japanese.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers held their position on Bennet’s Hill near Aberdeen until mid-afternoon on Christmas Day, when Gen. Maltby decided further resistance was futile and ordered the surrender.

For the captured Canadians, the horrors did not end there. Their treatment in prisoner camps in Hong Kong and Japan was atrocious. Almost as many Canadians died in the prison camps over the next four years as died in the battle for Hong Kong.

There is, however, a poignant postscript to this story.

On August 30, 1945, British Admiral Cecil Harcourt arrived in Hong Kong on his flagship, aircraft carrier HMS Colossus, to take the surrender of the Japanese and set up an interim military command. On Harcourt’s immediate staff was a Canadian of Chinese heritage from Victoria, Commander William Law.

Twenty years ago I spent two days with Law in Hong Kong, where he had set up as a lawyer after the war, married a local woman and raised his family. As Law recalled it, Harcourt, very much aware of the role of the Canadians in the defence of Hong Kong in 1941, delegated Law to be one of the first ashore.

The day after their arrival, Harcourt delegated Law to find the prisoners of war, who were being held in terrible conditions in former British barracks at Sham Shui Po on the Kowloon side. Law told me he took two Petty Officers, went over to Kowloon on the Star Ferry and marched up to the Peninsula Hotel, where they confronted the Japanese Chief of Police. He was persuaded to give Law and his men a car and a driver who knew the way to the camp.

When they arrived at the gates of the camp the Japanese guards levelled their rifles at the car. Law ordered the Petty Officers to aim their pistols out of the car windows and the driver to burst through the gates.

They did, and once inside Law went to the first barracks building on his left. He went into the darkened room and several of the prisoners from the Royal Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers looked up at him, but didn’t react.

“I guess they saw an Asian-looking guy in a uniform and thought I was just another Japanese officer,” Law told me.

“So I said, ‘What’s the matter with you guys? Don’t you know a Canadian when you see one?’”

Copyright Jonathan Manthorpe 2016

Contact, including queries about syndication/republishing: jonathan.manthorpe@gmail.com

~~~

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

~~~

Real journalism is not free. If you value evidence-based, non-partisan, spam-free information, please support organizations like Facts and Opinions, journalism for the public interest instead of to capture and sell your attention to advertisers or promote a cause other than democracy.