DEBORAH JONES: FREE RANGE

Published November 11, 2013

Accounts of Canadian John McCrae, who wrote In Flanders Fields, suggest a man steeped in the romance of war. McCrae was a physician as well as a poet, and also a warrior so dedicated that after fighting in the Boer War he enlisted for World War I. “He considered himself a soldier first,” says Wikipedia, in a quote attributed to a McCrae biographer. “McCrae grew up believing in the duty of fighting for his country and empire.”

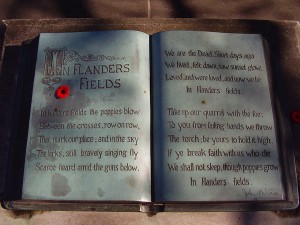

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

McCrae wrote his short poem, now as intricately bound with Remembrance Day as are red poppies, in honour of a friend who died in 1915 in the Second Battle of Ypres. That fight, already horrifically gory from traditional artillery, was made agonizingly worse by German chlorine gas, in one of the first modern uses of chemical weapons.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

It’s at Ypres that my imagination falters, along with my tenuous grasp of McCrae’s identity, and interest in the tiresome debate over the merits and meanings of his poem. It’s because of Ypres I am unable to imagine a man with the sensitivity of a poet and the intelligence of a physician harbouring “romantic” notions of war in the conditions of 1915 trench warfare. It’s harder to imagine even the soul of a soldier finding romance in war three years after Ypres – after the stark horrors of the “Great War” had long been plain – when McCrae died in 1918 of complications from pneumonia.

But our imagination quavers and warps in the face of war. Individual or collective memories are no match for it, and are besides often suppressed, leaving us only with imagination. Imagination of the worst kind, the kind that finds voice in nostrums like “glory,” “duty,” and “hero.”

Almost alone in my family I have never been a soldier, but I have studied war history and, like almost all of us, I am a child of generations of men and women who waged war. I am also the mother of children who astonished me by signing up as “peacekeepers” in the Canadian Army Reserves. Like almost all of us, I am closer to war than I’d wish. And yet I must resort to imagination to consider the wartime identity of the Scottish grandfather I barely knew, the Black Watch soldier who survived the trenches of WWI. Afterward he refused to speak of it and so, when I was a child, I imagined him a “hero.” Similarly, I could only imagine the thwarted life of a distant English cousin who was gassed as a young man in WW I and (according to hushed family reports) spent his few remaining years writhing and gibbering in a bed in his mother’s house. “Duty” was my childish word for him.

I like to think my imagination matured and that nuance replaced my nostrums for war.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Was McCrae’s bequest more nuanced than the nostrum we have made of his poem, faithfully recited each Remembrance Day? Had McCrae lived to write more poems post-war, would In Flanders Fields have been supplanted by a different work? Had he survived long enough might McCrae – especially after the futility of WWI was revealed by its reiteration in World War II – have changed his exhortation, “Take up our quarrel with the foe?”

I wonder if McCrae would have approved of being remembered so very well, so extraordinarily fondly, and so almost exclusively for In Flanders Fields. I wonder, but just a little, if his poem ought to be left in peace as a product of his time and place. Mostly I wonder if McCrae’s soldiers would rest better under their poppies if they knew that others had indeed caught the torch they threw – but used it not for foes and quarrels, but to shed light on war’s causes and cures.

We’ll never know what McCrae really thought; he died too soon and lingers only in our flawed imaginations. And that is just one of the infinite small shames buried within the immense disgrace of our warmongering.

Copyright © 2013 Deborah Jones

References and further reading:

In Flanders Fields Wikipedia page

McCrae House page, at the Guelph Civic Museum

Related:

National Peacekeepers’ Day, Deborah Jones, August 2016

Far from Flanders Fields, Deborah Jones, Nov. 2013

World and War, Deborah Jones, 2014