JONATHAN MANTHORPE: International Affairs

June 11, 2016

It is unlikely that Britons are going to give a conclusive answer to the question whether they should remain in the European Union or leave it when they mark their referendum ballots on June 23.

Recent polls show “Leave” supporters marginally ahead of those wanting to stay. The pro-“Brexit” vote is between 45 per cent and 48 per cent, according to half a dozen polls. The vote to remain is about five percentage points less.

But a poll published on Thursday and conducted by the market research company Opinium in tandem with the European Centre for Research in Electoral Psychology shows that about 18 per cent of voters are undecided. Most of those don’t expect to make up their minds until the last few days of the campaign.

So there is still everything to play for and the result is likely to be only a marginal victory for which ever side comes out on top.

Please chip in at least .27 cents to continue reading. Real journalism — reporting and analysis — is not free, and it’s not supported by either governments or the tooth fairy. Details below, or click here.

This will leave Britons divided about the future of the country. Though, given the nature of the campaign debate and the leading characters involved, muddled is probably a better description of the British state of mind. “Divided” implies passionately held views whose advocates will take years to resolve their differences, if they ever do. Yet these months of campaigning have been a singularly bloodless affair, notable more for the eccentricities of the leading figures involved than any sense that Britain’s long and colourful history is approaching a decisive moment.

The issues appear straightforward. The Brexit campaign says that since the EU morphed from being a purely free trade area into a political project aimed at creating a European federation, more and more sovereignty has slipped from Westminster across The Channel to Brussels. Britons, say the Brexit campaigners, are no longer masters in their own home.

The “Leave” campaign has focused on immigration and the free movement of people to live and work in any of the 28 countries of the EU. Immigrants are taking jobs from Britons and driving down wages, say the Brexiters. Mistrust of foreigners has taken hold with many voters despite independent analyses showing that Britain has a shortage of skilled workers and that this is driving up wages.

And voters should not fear that leaving the EU will have dire economic consequences, says the “Leave” campaign. Britain will easily sign free trade agreements with the old Dominions like Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as with the United States, and, indeed, with the EU as Switzerland and Norway have done.

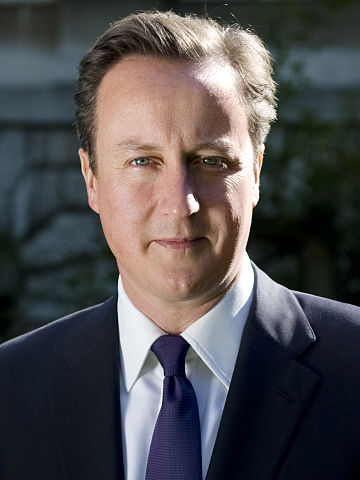

The Britain Stronger in Europe campaign is a cross-party group led by Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron. It has focused largely on what it says will be the terrible economic buffeting Britain will take if it leaves the EU. The “Remain” campaign is backed by a strong chorus of bankers, business leaders, economists and men-in-suits of various disciplines.

But these legions of doomsayers have not had a conclusive effect on the voters, largely because Cameron’s campaign has brought new depth of meaning and nuance to the word anaemic. His arguments have been made with such turgidity that Cameron deserves to lose the referendum just for being so incredibly boring.

Turgidity seems to have been his strategy. Cameron fears that if any passion or colour is injected into the campaign it would benefit only the Brexit side. He has made it firmly clear to his 27 fellow EU leaders as well as the union’s senior officials that he wants them to stay out of the debate. People like German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, have buttoned their mouths at Cameron’s insistence. They have been left with the clear feeling Cameron thinks that any expression of hope on their part that Britain stay in the EU will be counterproductive and only bolster the Brexit side. For that reason, Cameron was not happy when, a few weeks ago, U.S. President Barack Obama urged Britons to stay in the EU.

With such a lacklustre campaign advocating “Remain,” it is a wonder the polls show both sides so evenly matched. That must be because the champions of Brexit are a cast of characters from whom anyone with any sense would hesitate to buy a used car.

The British public’s affection for Boris Johnson, the former Mayor of London and now Tory backbencher who made a political career by playing a loveable, naughty sheepdog, appears to be wearing thin. His dishevelled appearance and colourful refusal to abide by rules of political correctness have carried him this far. But in retrospect, his eight years as Mayor of London, which ended early in May, were singularly unproductive. There is no doubt that his main aim in leading the Brexit campaign is to oust Cameron as Tory leader and become the British Prime Minister. And with Johnson, there is always a problem about believing what he says. He is singularly untrustworthy, and his path through life is littered with friends, and especially women, whom he has betrayed.

Boris as TV personality, and even as mayor, is entertaining, but do you really want him in 10 Downing Street and leading Britain along the lonely post-EU path into the unknown?

Nigel Farage, the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party – Ukip – has lengthy credentials as a champion of the campaign to get Britain out of the EU. Oddly in the circumstances, his main political platform is as a long-running Member of the European Parliament. His several attempts to get elected to the Westminster Parliament have failed, but voters pay far less attention to whom they send to the Strasbourg parliament. A small, highly organized campaign can often win a seat in the European Parliament, which is why it contains more than its fair share of odd balls.

Farage appeals to hardcore Little Englanders, but for most people he is the pub’s loudmouth bore — entertaining for about five minutes on first meeting, and then to be shunned.

What no one has figured out with any certainty is what happens on June 24 if a majority of British voters opted to leave the EU the day before. There is a mechanism for EU members to leave under Article 50 of the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon. This envisages a two-year period when the remaining 27 EU members would negotiate Britain’s departure. The ignominy of this would be that Westminster would lose the initiative. Its exit voucher would be a matter of bargaining and squabbling among the other 27.

And the two-year timetable is not hard and fast. It can be extended, and it is easy to imagine that the EU’s most powerful members and institutions would see it in their interest to stall the process for as long as possible. There are real fears that Brexit might spark a rush for the exit by other countries that are unhappy with loss of sovereignty and governing powers to Brussels. There are even predictions that Britain’s departure could trigger the collapse of the entire EU, especially as a political federation. Thus, in the EU bureaucracy and pivotal countries like Germany and France there will be no desire to make Britain’s departure easy, quick or painless.

There is also the prospect that a vote to leave could start the break-up of the United Kingdom. The Scots in particular are strong supporters of EU membership. A Brexit vote would undoubtedly encourage the Scottish Nationalist regional government to launch another referendum on Scottish independence, this time with more likelihood of winning than in the 2014 ballot.

Cameron has said that if the leave faction wins on June 23 he will invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty – before himself heading off into political retirement. But there is another route Britain can go if the Brexit vote wins. The Westminster parliament can simply repeal the 1972 European Communities Act that enabled Britain to join what was then the European Economic Community. It is far from certain, however, that the British Parliament would back a unilateral declaration of independence from the EU.

Cameron was pressed into staging this referendum because of pressure from his backbenchers, about half of whom support Brexit. But in the House of Commons as a whole, there is a clear majority that wants Britain to remain in the EU. If there is only a slim majority for Brexit, and especially if there is a low voter turnout, MPs can justifiably question the political legitimacy of the result and balk at revoking the European Communities Act.

Thus a vote for Britain to leave the EU is unlikely to produce a “Freedom at Midnight” moment. Instead it will open the gate to a long and gruelling trudge through a muddy field, with no clear view of the destination or what the eventual outcome will be.

Copyright Jonathan Manthorpe 2016

Contact: jonathan.manthorpe@gmail.com. Please address queries about syndication/republishing this column to jonathan.manthorpe@gmail.com

Further information sources:

- European Union site: http://europa.eu/index_en.htm

- The UK’s EU referendum: All you need to know, By Brian Wheeler & Alex Hunt, BBC News: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-32810887

- United Kingdom withdrawal from the European Union, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Kingdom_withdrawal_from_the_European_Union

- UK’s EU referendum, Financial Times: http://www.ft.com/eu-referendum

- Brexit | The Economist: www.economist.com/Brexit

- Der Spiegel interview with Wolfgang Schäuble, German finance minister: http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/spiegel-interview-with-wolfgang-schaeuble-on-brexit-a-1096999.html

- France24: compiled Brexit stories: http://www.france24.com/en/search/?Search%5Bterm%5D=Brexit&Search%5Bpage%5D=1

- Deutsche Welle: compiled Brexit stories http://www.dw.com/search/en/brexit/category/9097/?

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

Jonathan Manthorpe is a founding columnist with Facts and Opinions and is the author of the journal’s International Affairs column. He is the author of “Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan,” and has been a foreign correspondent and international affairs columnist for nearly 40 years. Manthorpe’s nomadic career began in the late 1970s as European Bureau Chief for The Toronto Star, the job that took Ernest Hemingway to Europe in the 1920s. In the mid-1980s Manthorpe became European Correspondent for Southam News. In the following years Manthorpe was sent by Southam News, the internal news agency for Canada’s largest group of metropolitan daily newspapers, to be the correspondent in Africa and then Asia. Between postings Manthorpe spent a few years based in Ottawa focusing on intelligence and military affairs, and the United Nations. Since 1998 Manthorpe has been based in Vancouver, but has travelled frequently on assignment to Asia, Europe and Latin America.

~~~

Real journalism is not free. If you value evidence-based, non-partisan, spam-free information, please support Facts and Opinions, an employee-owned collaboration of professional journalists. Details here.

![]()

F&O’s CONTENTS page is updated each Saturday. Sign up for emailed announcements of new work on our free FRONTLINES blog; find evidence-based reporting in Reports; commentary, analysis and creative non-fiction in OPINION-FEATURES; and image galleries in PHOTO-ESSAYS. If you value journalism please support F&O, and tell others about us.